College Affordability Remains Out of Reach for Immigrants of Color Throughout Generations

Published Oct 11, 2024

Last year, we reported that students of color were more likely than White students to face a gap between their total college costs and the financial assistance available to them from grants and family resources, also known as unmet need. Our new analysis of unmet need finds a compelling pattern — college affordability is stratified not just at the intersection of race and ethnicity, but also by immigration background, with immigrants of color, particularly Black immigrants, facing high unmet need throughout generations.

Immigrants and their descendants make up a critical and growing segment of college students, comprising 34% of total enrollment, according to new IHEP analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education’s 2019-20 National Postsecondary Student Aid Survey (NPSAS:20). This includes 11% of students identifying as immigrants and an additional 23% reporting one or both parents born outside of the United States. In 2015-16, just 30% of students were immigrants or children of immigrants.

Immigrant students and their descendants face many barriers that limit their access to and success within the postsecondary system. These include disproportionate levels of poverty, difficulty navigating the complex American financial aid system, systemic racism and K-12 funding disparities, and restrictions some states place on who can qualify for financial aid and work-study opportunities based on documentation status.

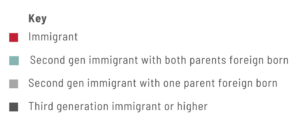

The charts and analyses below examine how unmet need differs by immigrant students’ race and generational status: those born outside the United States (immigrant students); U.S.-born students with one or two foreign-born parents (second generation); and U.S.- or foreign-born students with U.S- born parents (third generation or higher). Our findings demonstrate the importance of considering affordability data for discrete populations over time.

The charts and analyses below examine how unmet need differs by immigrant students’ race and generational status: those born outside the United States (immigrant students); U.S.-born students with one or two foreign-born parents (second generation); and U.S.- or foreign-born students with U.S- born parents (third generation or higher). Our findings demonstrate the importance of considering affordability data for discrete populations over time.

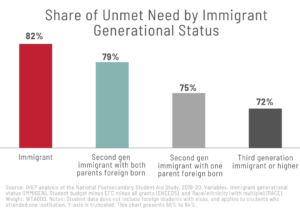

Data Disaggregation Shows Disparities in Immigrant Students’ Unmet Need by Race and Ethnicity

The broad data suggests that unmet need decreases with each generation. Data from 2019 showed that 82% of first-generation immigrant students faced unmet need, a figure that declined to 72% for those third generation or higher.

However, disaggregating by race and ethnicity in addition to immigrant generational status illuminates a different reality. First-generation Asian, Black, and Hispanic or Latino immigrant students all had notably higher shares of unmet need, at 83%, 86% and 85%, respectively, than White first-generation immigrant students (74%).

There were also differences over time. While White and Asian immigrant families had substantial decreases in share of unmet need over generations, Hispanic or Latino immigrant families showed only minor decreases. Over 80% Hispanic or Latino students still faced unmet need even in the third generation or higher.

For Black immigrant families, share of unmet need actually increased over generations, with a whopping 88% of Black third-generation or higher students facing unmet need, two percentage points higher than Black first-generation students.

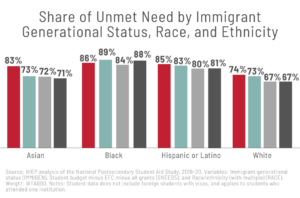

Black Immigrant Students Face Highest Unmet Need Generations After Arrival

Similar trends emerged when we looked at the average amount of unmet need: it tended to be highest for immigrant students and to decrease with each generation, with variations by race and ethnicity. For example, Hispanic or Latino immigrant students faced $6,574 average unmet need, a figure that dropped to $5,375 for third-generation or higher students. White immigrant students faced the lowest average unmet need at $3,442; third-generation or higher White immigrant students were typically able to fully cover college costs with about $805 to spare. Among second-generation immigrant students across all racial and ethnic groups, having both parents foreign born was associated with higher average amounts of unmet need compared to having one foreign-born parent.

But again, the situation for Black immigrant students was considerably different when we examined trends over time. Black immigrant students faced the highest average unmet need by a considerable margin, at $9,106, and that burden remained high ($8,893) even for Black students who had been in the U.S. for three or more generations.

This data suggests that with more time to adjust to life in United States, some immigrant families have increased access to financial resources for college. However, for the Black, Hispanic or Latino, and some Asian immigrant families whose unmet need continues to total thousands of dollars in subsequent generations, barriers related to systemic racism may be masking or offsetting these gains.

The Importance of Considering Immigrant Generational Status in Research and Policymaking

For many immigrants to the United States and their families, higher education offers a pathway to continue careers established in their native countries or to pursue new opportunities. Improving access and affordability for immigrant students and their families is essential if institutions and states want to achieve their enrollment, completion, and workforce development goals.

Disaggregating by immigrant generational status shows that students can face barriers to college access even generations after their arrival in the United States, particularly if they are Black, Hispanic or Latino, or Asian. Policymakers and researchers should consider what additional practices would best serve students who face systemic barriers in college access at the intersection of immigrant generational status, race, and ethnicity. Policies that increase financial aid for students from low-income backgrounds, such as doubling the Pell Grant and funding first-dollar free college programs, are positive steps to increase college affordability for all students.