Legacy Looms Large in College Admissions, Perpetuating Inequities in College Access

Published Jul 01, 2024

A year ago, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the use of race-conscious admissions in higher education. Yet legacy admissions policies that give preferential treatment to applicants who are related to alumni are still used across the country. A new IHEP analysis of data released through the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) reveals the prevalence of legacy admissions policies among selective colleges and universities. The data indicate that considering legacy status when making admissions decisions is associated with decreased college access for Black and Hispanic students, as well as for students living with low incomes.

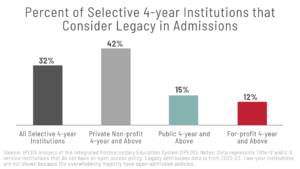

How widespread are legacy admissions policies?

Nearly one third of all selective four-year institutions in the U.S. considered legacy status for first-time students enrolling in fall 2022. These policies were especially prevalent at selective private nonprofit four-year institutions, 42 percent of which considered legacy status. Fifteen percent of selective public four-year colleges also considered an applicant’s family ties to the institution when making admissions decisions, encompassing a large share of the students who are affected by legacy status in admissions. In the 2021-2022 academic year, 2.1 million undergraduate students enrolled in institutions that considered legacy status when making admissions decisions. Public four-year colleges accounted for nearly 2 in 5 of those students.

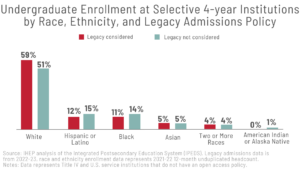

When colleges consider legacy in their admissions process, they prioritize access for children of college-educated families who are disproportionately White and well-off. Giving a leg up to the relatives of college graduates perpetuates this trend in succeeding generations, tilting the scales against Black and Hispanic students and students from low-income backgrounds. The use of legacy preferences and other inequitable recruitment, admissions, and enrollment practices undermines the mission of public colleges to serve as pathways to economic mobility for state residents.

Black and Hispanic students, and students who receive Pell Grants enroll in institutions that consider legacy in admissions at lower rates

The most recent IPEDS data reveal disparities by race, ethnicity, and income in college enrollment between institutions that consider legacy in their admissions process and institutions that do not. Selective institutions that do not consider legacy in admissions are more racially diverse, with higher proportions of Black and Hispanic students compared with selective institutions that do consider legacy status in admissions. American Indian or Alaska Native enrollment differs by one percentage point between both categories, while enrollment of Asian students and students who identify as two or more races remained the same in both cases. Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander enrollment data are not included in this analysis due to small sample sizes, nor are enrollment data for students of unknown race or who are not U.S. residents.

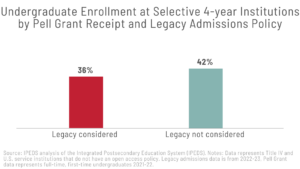

Similarly, selective four-year institutions that do not consider legacy status serve a greater share of students from low-income backgrounds. Forty-two percent of full-time, first-time undergraduates at these institutions receive Pell Grants, a federal need-based aid program, compared with just 36 percent at selective four-year institutions that do consider legacy in admissions. Students who are the first in their families to attend college are particularly disadvantaged by legacy admissions policies because their parents have not earned a degree.

Colleges should end legacy admissions policies to expand college access

Last year’s U.S. Supreme Court decision to end race-conscious admissions in higher education underscores the urgency of expanding college access by eliminating inequitable recruitment, admissions, and enrollment policies. The decision has fueled increased scrutiny of legacy admissions, prompting policymakers in several states to introduce legislation to end the practice. Over 100 institutions have eliminated legacy policies since 2015, and three states have banned legacy admissions at public institutions. But as this analysis shows, more action is needed to expand access at selective institutions, particularly for students who have been historically marginalized on the basis of race or income.

To diversify student populations, enrich learning communities, and deliver educational excellence to all students, institutions should stop considering legacy status when making admissions decisions and instead consider whether students are the first in their family to go to college. Additional admissions guidance or financial support should be targeted to first-generation students and students from low-income backgrounds.

The U.S. Department of Education’s release of legacy admissions data is a commendable first step in providing an evidence base for postsecondary leaders to rethink their policies and practices to prioritize equitable access. The Department has also proposed collecting data on applicants and admitted students, disaggregated by race and ethnicity. As researchers continue examining how the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision is impacting enrollment, these new data will deepen the field’s understanding of this issue and strengthen efforts to address systemic inequities in college admissions.

Read IHEP’s 2021 report The Most Important Door That Will Ever Open: Realizing the Mission of Higher Education Through Equitable Recruitment, Admissions and Enrollment Policies and take action now with the legacy admissions advocacy tool.

___

Editor’s Note: This post has been updated to clarify that nearly one third of all selective four-year institutions in the U.S. considered legacy status for students enrolling in fall 2022, not for students enrolling during the 2021-2022 academic year.