Layers of Identity: Rethinking American Indian and Alaska Native Data Collection in Higher Education

Published May 2024

All people deserve the opportunity to earn a better living and build a better life for themselves, their families, and their communities through a postsecondary education. But that opportunity is not available equally to all in the United States, and current postsecondary data sets and collection practices at the federal, state, and institutional levels can both lack information on or inadvertently mask disparities in college access and success for different student populations—particularly those from Indigenous communities.

Identity comprises intricate and complex layers not always captured by the aggregate racial and ethnic categories used in postsecondary data sets. The political, legal, and cultural significance of American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) identity requires careful attention to the collection of AI/AN student data. Federal racial and ethnic categories have not historically captured the nuances of AI/AN identity, though new federal standards announced in March 2024 will improve the collection of data on AI/AN populations. This will have consequences for how states and institutions collect and report AI/AN data to federal postsecondary data collections and on how that data are presented.

In this brief, the term “American Indian and Alaska Native” or “AI/AN” will be used when referring to individuals who would be categorized as AI/AN in federal data sets. However, we are mindful that this term can limit the prospects of Native identity. While all individuals identifying as AI/AN are Indigenous, not all Indigenous individuals are counted as AI/AN in data sets. To encapsulate the entire community, the terms “Indigenous” and “Native” will be used to refer to the broader populations.

Currently, the U.S. has 574 federally recognized Tribes, and many more that are state recognized or are not recognized at all.1 Each Tribe has its own culture, geography, and language. While there is incredible diversity within Indigenous communities, most data sets and collection practices do not capture culturally relevant data points, which can lead to inconsistent or overgeneralized analyses. High-quality data that can be disaggregated beyond just race and ethnicity and by key characteristics that are significant to cultural communities can help identify and remove barriers for students. Policymakers need high-quality data to inform policies geared towards increasing college access, persistence, and completion rates for AI/AN students.

Unlike other racial groups that are defined in federal data collections, the AI/AN category is both a political and legal classification.2 Individuals identifying as AI/AN may hold Tribal citizenship in Native Nations that have a nation-to-nation relationship with the United States government.3 This relationship has implications for how these students navigate their postsecondary journey. However, distinctions between Tribal members are not consistently reflected or incorporated into postsecondary data sets due to inadequate disaggregation by Tribes, lack of stratified sampling, and/or insufficient consultation with Tribal communities. Moreover, the way federal data sets have historically categorized multiracial and multiethnic AI/AN students has contributed to the erasure of Indigenous students from data sets, complicating the presentation and analysis of information about AI/AN students.4 The new federal race and ethnicity standards offer improvements, particularly for the categorization of AI/AN students with Hispanic ancestry, and federal agencies will have until March 2029 to implement those changes.

This brief focuses on individuals categorized as AI/AN in federal data sets and highlights the complexities of collecting data about this community, including how AI/AN students are counted and categorized in data collections and how those collections fall short in engaging and representing Indigenous communities. Because of current data collection practices, educators, researchers, and policymakers lack the information needed to challenge the barriers Native students face and to ensure that Indigenous students are well served in higher education. This brief proposes strategies for federal agencies, states, institutions, and researchers to use to improve the collection, reporting, and analysis of AI/AN student data. These strategies prioritize actively engaging with Tribal leaders and Indigenous researchers and organizations to identify ways to improve data collection and reporting procedures. These improvements can increase the quality of data analysis and reporting about AI/AN students and more accurately and thoroughly showcase the diverse subgroups within the Indigenous community.

Who is Counted as American Indian/Alaska Native?

All federal postsecondary data collections use Office of Management and Budget (OMB) standards for the classification of federal data on race and ethnicity.5 Under OMB’s previous standards, AI/AN was defined as a “person having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America (including Central America) and who maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment.”6 In March 2024, OMB released revised federal race and ethnicity standards that define AI/AN as “Individuals with origins in any of the original peoples of North, Central, and South America, including, for example, Navajo Nation, Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana, Native Village of Barrow Inupiat Traditional Government, Nome Eskimo Community, Aztec, and Maya.”7 The new standards remove the language “who maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment” from the AI/AN definition and require the default collection of detailed race and ethnicity categories, which could include Tribal affiliation. OMB’s updated guidance was informed by public listening sessions, which included a Tribal consultation with Tribal leaders and members.

Categorization of Multiracial or Multiethnic AI/AN Students in Federal Data Sets

Additional complications with the analysis of AI/AN data have arisen due to OMB’s former definition of Hispanic or Latino individual and the categorization of students identifying with more than one race or ethnicity.

Previously, OMB designated a Hispanic or Latino individual as “a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race.”8 Under that definition, any AI/AN student with Hispanic ancestry would be automatically categorized as Hispanic or Latino in federal data collections, regardless of Tribal affiliation and involvement. This practice results in an undercount of the AI/AN population and diminishes the ability of researchers, policymakers, and Tribal nations to fully understand trends among Indigenous students.9 OMB’s new standards remove “regardless of race” from the Hispanic or Latino definition and require federal agencies to use a single combined question for race and ethnicity.10  When those standards are adopted, AI/AN students with Hispanic ancestry will no longer automatically be subsumed into the Hispanic or Latino category.

When those standards are adopted, AI/AN students with Hispanic ancestry will no longer automatically be subsumed into the Hispanic or Latino category.

In addition to the challenges of identifying AI/AN students with Hispanic ancestry or origins, there are also complications with identifying multiracial AI/AN students. In recent decades, there has been an increase of multiracial individuals who identify as Indigenous. Between 2010 and 2020 alone, the percentage of individuals who identified as AI/AN in combination with another race increased by 160 percent.16 Students who mark more than one race in federal postsecondary data collections, even if they are Tribal citizens, are often categorized as “Two or More Races”.17 As a result, multiracial AI/AN students are often not counted under the AI/AN category, regardless of their Tribal citizenship or level of involvement with Tribal communities. At a granular level, this means that multiracial AI/AN students and their experiences are being overlooked.18 OMB’s revised standards describe two approaches for presenting data on race and ethnicity that would allow for the identification of multiracial AI/AN individuals (e.g., those who are AI/AN alone or in combination with another racial or ethnic group).19

Methods of Identifying AI/AN Populations

Two primary methods are used to identify and count AI/AN individuals in higher education: self-identification and Tribal enrollment verification. Each approach has benefits and limitations, and they are not mutually exclusive. When considering these approaches, it is important for researchers, policymakers, and institutional leaders to understand the trade-offs and implications associated with each.

Self-Identification

In most postsecondary data collections, students self-identify ethnic and racial affiliation, usually upon enrollment in college, by simply marking a box that best reflects their identity.20 This approach affirms an individual’s sense of self, accounting for those who consider themselves AI/AN and encompassing both enrolled members of a Tribe as well as individuals with cultural and communal affiliations with a Tribe, but who may not be enrolled as Tribal citizens.

However, self-identification can open the door to potential misuse. Individuals might misrepresent their background with hopes of gaining access to resources and services that are designated for AI/AN students.21 There is also potential for inconsistency. How students are categorized across data collections may differ if they do not report their race or ethnicity the same way each time.

Using self-identification to count AI/AN individuals can also present challenges to Tribal sovereignty over citizenship criteria. Tribal Nations have the sole authority to determine who is and is not a citizen, and self-identifying as AI/AN is not sufficient for citizenship.23 Generally, eligibility for citizenship includes being descended from a Tribal citizen and/or meeting a blood quantum threshold, though this varies from Tribe to Tribe.24

Verification of Tribal Enrollment

Tribal Nations collect and maintain data on enrolled members of their Nations as a means of asserting Tribal sovereignty and building Native Nations.25 Tribal citizens are provided with documentation to verify their enrollment in a Tribe. In addition to asking students to indicate Tribal affiliation, colleges and universities may require students to share this documentation to verify citizenship. This verification process aids schools in gaining a deeper understanding of AI/AN demographic trends; provides informed, disaggregated Tribal data to Tribal leadership; and grants access to programs or resources specifically designated for AI/AN students.

Tribal enrollment information can be collected at both the state or institutional level during enrollment or within financial aid application processes. Several states and colleges offer tuition waiver programs for AI/AN students and require that students provide documentation to verify their enrollment in a federally or state-recognized Tribe.26 For example, the Oregon Tribal Student Grant, administered at the state level, provides funding for Oregon Tribal students to cover the average cost of attendance for Oregon public colleges and universities and requires that students submit a Tribal Enrollment Verification form in addition to their application.27 Similarly, at the University of Arizona, enrollment documentation can be requested for a student to qualify for the Arizona Native Scholars Grant, an institutional program that covers tuition and fees for Native undergraduate students who are Arizona residents and are seeking their first bachelor’s degree.28 This approach to identifying AI/AN students upholds Tribal sovereignty and addresses concerns over non-AI/AN students falsely claiming AI/AN heritage.

However, requiring Tribal enrollment documentation can also create hurdles for students, and it excludes students who may have cultural and communal affiliations with a Tribe but are not enrolled citizens in a federally or state-recognized Tribal Nation.29 Even those who are members of a recognized Tribe may face difficulties in presenting acceptable documentation. For example, students may lack access to the technology needed to upload a copy of their enrollment paperwork. In fact, about 11 percent of Native children did not have internet access in their homes in 2021, a staggering disparity when compared to the national average of 3 percent.30 This digital divide is more pronounced on Tribal lands, where only 68 percent of residents had at-home high-speed internet in 2019.31

What are the limitations of current data collections on AI/AN students?

The definitions and methods used to classify AI/AN students create obstacles that have compounding consequences on the overall quality of data about AI/AN students. Three key limitations that arise are: small counts, inconsistent classification of AI/AN students, and overgeneralized representations of AI/AN communities.

Small Counts

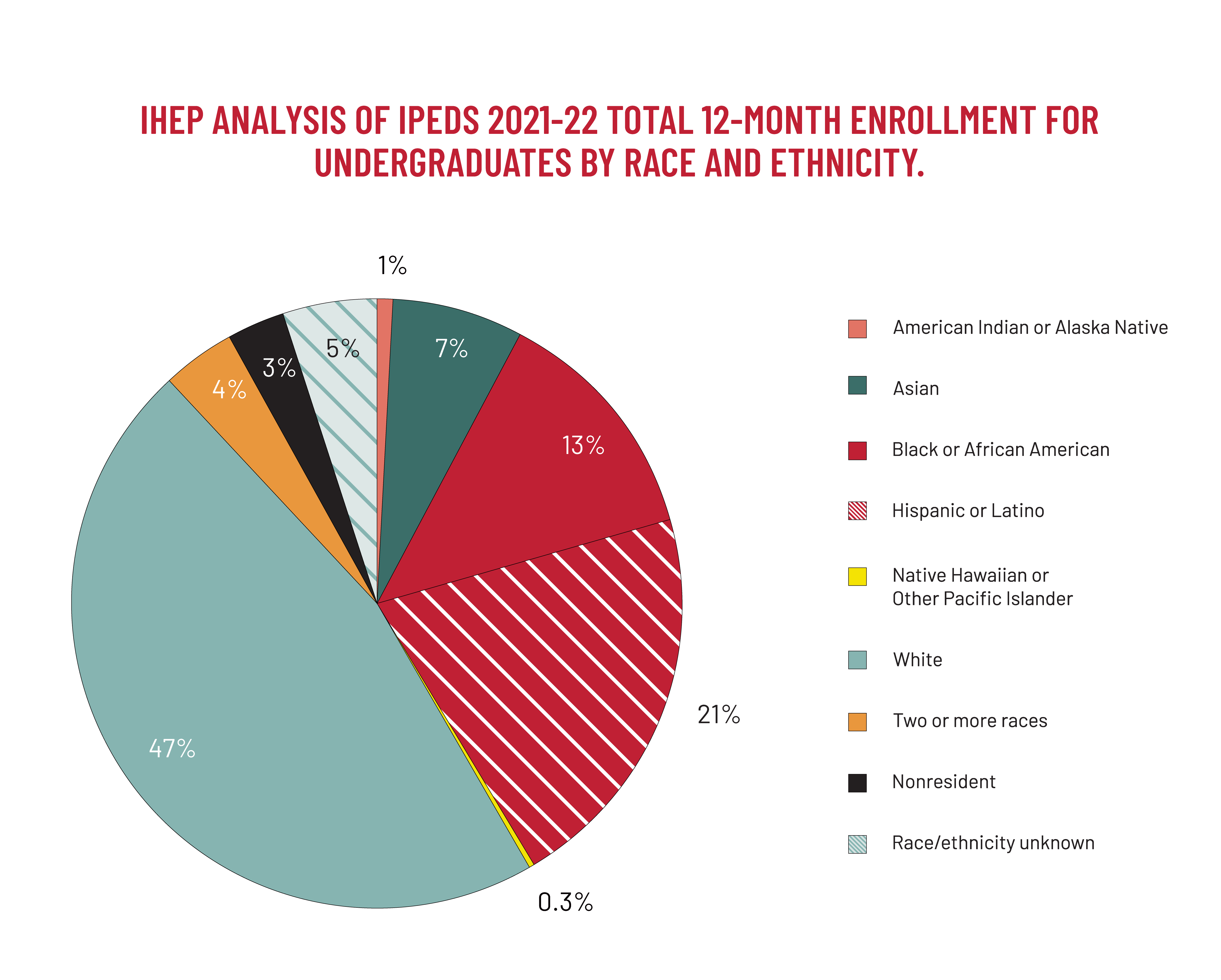

Small population sizes of AI/AN students pose major challenges for Tribal nations, researchers, and policymakers alike. The severe underrepresentation of AI/AN students in higher education is due to a combination of factors such as college affordability, lack of curricula or academic programs that incorporate Indigenous knowledge, gaps in recruitment efforts and culturally informed wraparound services, and college access and retention supports for Indigenous students.32 These obstacles, compounded by the undercounting of AI/AN students with Hispanic or Latino ancestry and of multiracial AI/AN students, exacerbate the issue of small AI/AN population sizes in higher education. As a result, AI/AN students only made up 1 percent of the total undergraduate population in 2021–22 (see pie chart below) in the U.S.33 This underrepresentation and undercounting means that the number of students researchers are using in analyses is much smaller than for other racial groups, making it more difficult to accurately represent AI/AN students and their experiences.34

Methodological challenges stemming from small sample sizes often lead researchers to either omit findings about AI/AN students, collapse them into a catch-all category with other groups, or mark data trends specific to AI/AN populations with an asterisk.35 This can suggest to readers that data on the population are insufficient, lacking, or nonexistent.36 These practices mask the specific needs and experiences of AI/AN students in higher education, preventing institutions from addressing their particular circumstances.

Researchers can employ different strategies to overcome these challenges. These strategies include oversampling AI/AN students and stratifying across Tribes, a process that involves building a representative sample group from the different subpopulations within the community. Researchers also should collaborate with Tribes and Indigenous researchers to formulate culturally relevant and nuanced research or survey questions. These efforts can enhance survey response rates among AI/AN students, increase the statistical power of sample sizes, and improve the quality of data for use by Native Nations and policymakers.37 Additionally, OMB’s revised federal race and ethnicity standards may reduce the undercounting of AI/AN students when fully implemented, particularly for AI/AN students with Hispanic ancestry.

Aside from the percentage of the “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” category, all other percentages are rounded to the nearest degree.

Inconsistent Classification

Longitudinal and trend data help assess the effectiveness of policies and practices. However, inconsistent definitions, measurement techniques, and reporting standards make it difficult to derive reliable findings about how effectively policies are supporting AI/AN students in postsecondary education. The U.S. federal government has revised its definitions and collection methods for the AI/AN racial category four times since 1950. Shifting how individuals are defined in a racial group makes it challenging to assess the impact of policy.38

Moreover, individuals with a fluid notion of self-identity may not consistently identify as AI/AN across different data collections or may self-report differently depending on how an institution has crafted its survey questions. This leads to fluctuations in the number of AI/AN students counted from one survey to another.39 And, because there is no clear standard on whether to use self-identification or Tribal enrollment as an indicator of AI/AN status, results can vary across institutions, states, or time simply because of adjustments in measurement approach. In fact, there is a long history of unreliable AI/AN enrollment counts, spanning both the precollegiate and postsecondary levels.40 But while data collection practices should adapt to changes in the ways identity is constructed, each alteration must be carefully considered alongside ways it will diminish the accuracy of long-term trends.41

Overgeneralized Representations of AI/AN Communities

As with all racial and ethnic communities, the AI/AN population is incredibly diverse. Aggregating data can mask differences in educational outcomes between hundreds of Tribes, all of which differ in complex and nuanced cultural, geographical, and political ways. The number of citizens per Tribe ranges from below 100 to over 450,000, with smaller Tribes more likely to be excluded in data collections.42 Omitting some Tribes and masking differences between others can make it easy for data users to make generalizations about AI/AN students and their communities, but these generalizations limit the ability of policymakers and practitioners to design policies and interventions that are reflective of and responsive to the distinctiveness of AI/AN communities. For instance, AI/AN students’ postsecondary experiences can vary based on Tribal recognition status and geographic location.43 Students who are members of federally or state-recognized Tribes can access supports like tuition waivers, whereas students from non-recognized Tribes have access to fewer AI/AN-specific resources and interventions. Similarly, because some reservations can span across several states, students living on the same reservation can be eligible for different programs, tuition rates, and financial aid.44

Access to data that acknowledges the cultural distinctions, recognition status, and geographical diversity between Tribes is imperative for shaping culturally responsive policies that can support student success. To create more opportunities for Indigenous students to access and succeed in postsecondary education, researchers and federal, state, and institutional leaders need to make data collections about AI/AN students more robust and reflective of the nuanced identity and history of the Native community.

How Can Data-sets and Collection Methods for AI/AN Students Improve?

Improving data sets and collection practices requires collaboration between researchers, institutions, and federal and state governments to engage Indigenous and Native communities so that Indigenous rights, needs, and aspirations are embedded in every part of the policymaking process.45 The recommendations outlined below outline steps researchers and federal, state, and institutional leaders can take to improve data collection.

Engage Indigenous researchers and Tribal communities in data collection methods and research

Policymakers, higher education leaders, and researchers must build, strengthen, and maintain strong relationships with Tribes and Tribal Leaders. These relationships will help ensure that data sets and collection practices are inclusive and better represent the various characteristics of the Indigenous community.46

1. Collaborate with local Tribes to update data collection methods.

Investing in relationships with Tribes and Tribal governments creates opportunities for states, institutions, and researchers to understand what culturally relevant data points would be helpful for Tribes to see in data sets. This knowledge can inform internal data collections and help institutions and states better understand the Tribal diversity of their AI/AN students, which supports Nation building and upholds Tribal sovereignty.

2. Ensure Tribal and Indigenous representation on advisory boards.

Governments and institutions need to make space for Tribal representation in more formal advisory settings like Technical Review Panels (TRPs). Soliciting input from Tribal leaders and Indigenous researchers on methodology is a key step to ensure that collection standards represent AI/AN students. Gathering feedback from Indigenous leaders can help policymakers and institutional leaders make data collections more reflective of the Native community.

Improve approaches for collection, reporting, and analysis of AI/AN student data

Amidst discussions about data collection practices for this population, researchers and institutional leaders and their research offices can take several key steps to improve current data and analysis on AI/AN students.

1. Incorporate Indigenous data collection methods.

Collaborate with Tribes and Indigenous researchers to ensure that data collection activities are culturally responsive and incorporate Tribal perspectives, which increases the quality of data collected and its usefulness for Tribal Nations.47

2. Oversample AI/AN students.

Oversampling helps to build sufficiently large sample sizes for robust data analysis. When possible, strive for samples that are representative of the Native community and are Tribally diverse.

3. Document limitations.

Researchers should clearly document limitations they encounter with AI/AN data and explain how those limitations were addressed. In cases where AI/AN student data are excluded from findings, provide a clear explanation for the decision.

Improve data sets and collection methods to better reflect AI/AN communities

Lastly, there are improvements that could be applied to federal and state data collections to improve the quality of data on AI/AN students.

1. Collect data on Tribal affiliation.

When possible, collections should gather information on students’ Tribal affiliation. Gathering these data points helps data users disaggregate information at a more granular level. Tribal-level data also allow stakeholders to make informed decisions regarding interventions, policies, and programs to support students’ academic success.

2. Collaborate with Indigenous leaders and Tribes when implementing OMB’s revised race and ethnicity standards.

OMB’s revised federal race and ethnicity standards, published in March 2024, provide a modified definition of AI/AN, require the default collection of detailed race and ethnicity categories, and combine race and ethnicity into a single question, among other changes.48 Within 18 months of the publication of those standards, the Department of Education (ED) and other federal agencies are required to develop Action Plans describing how they will bring their data collections and publications into compliance with the standards by March 28, 2029. In developing its Action Plan, ED should collaborate with Indigenous leaders and researchers to establish clear guidance on how to report AI/AN data to federal postsecondary data collections, including how to best present data on multiracial AI/AN students. This could involve conducting targeted listening sessions, including Indigenous leaders and researchers in Technical Review Panels, and soliciting their feedback in other ways.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the individuals and organizations who helped develop this brief, including Mamie Voight, IHEP president; Diane Cheng, vice president of research and policy; Kelly Leon, vice president of communications & government affairs; Sean Tierney, director of research and policy; Kim Dancy, associate director of research and policy; Lauren Bell, communications associate; Marián Vargas, senior research analyst; Charles Sanchez, research analyst; and Pearl Lo, former research and policy intern. We are incredibly grateful to Dr. Jameson D. Lopez for his review and guidance on the brief. We also thank Sabrina Detlef for copyediting and openbox9 for creative design and layout.

All ideas, findings, and conclusions drawn by this report are the sole responsibility of the report’s authors.

Endnotes

1 National Congress of American Indians. (2020, February). Tribal Nations and the United States: An introduction. https://www.ncai.org/about-tribes.

2 Evans-Lomayesva, G., Lee, J. J., & Brumfield, C. (2022, November). Advancing American Indian & Alaska Native data equity: Representation in federal data collections. Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality. https://www.georgetownpoverty.org/issues/advancing-american-indian-alaska-native-data-equity/

3 National Congress of American Indians. Tribal Nations and the United States.

4 Falkenstern, C., & Rochat, A. (2021, February). Better data for supporting American Indian/Alaska Native students. WICHE Insights. https://www.wiche.edu/resources/wiche-insights-better-data-for-supporting-american-indian-alaska-native-students/.

5 The United States Department of Education has published guidance on how to apply OMB’s standards for maintaining, collecting, and presenting data on race and ethnicity to education data collections. See its 14-page Federal Register notice from October 19, 2007, which implement OMB’s previous standards, at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2007/10/19/E7-20613/final-guidance-on-maintaining-collecting-and-reporting-racial-and-ethnic-data-to-the-us-department. Under OMB’s new federal race and ethnicity standards published on March 29, 2024, federal agencies, including the Department of Education, must develop and submit Action Plans for implementing the new guidance within 18 months from the publication of the notice. Read more about the updated guidance at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/03/29/2024-06469/revisions-to-ombs-statistical-policy-directive-no-15-standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and.

6 Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data, 62 FR 58782. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/1997/10/30/97-28653/revisions-to-the-standards-for-the-classification-of-federal-data-on-race-and-ethnicity; and United States Census Bureau (website). About the Topic of Race. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html

7 Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/03/29/2024-06469/revisions-to-ombs-statistical-policy-directive-no-15-standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and.

8 Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data, 62 FR 58782; United States Census Bureau (website). About the Hispanic population and its origin. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/hispanic-origin/about.html; IES-NCES (website). Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. Collecting race and ethnicity data from students and staff using the new categories. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/report-your-data/race-ethnicity-collecting-data-for-reporting-purposes; and IES-NCES (website). Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. Institutional responsibility for reporting race and ethnicity to IPEDS. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/report-your-data/race-ethnicity-reporting-changes.

9 Falkenstern, & Rochat. Better data for supporting American Indian/Alaska Native students.

10 Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, 89 FR 22182.

11 Walter, M., & Carroll, S. R. (2021). Indigenous Data Sovereignty, governance, and the link to Indigenous policy. In Walter, M., Kukutai, T., Carroll, S. R., & Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. (Eds.), Indigenous Data Sovereignty and policy (pp. 1–20). Taylor & Francis.

12 The University of Arizona Native Nations Institute (website). Indigenous Data Sovereignty and governance. https://nni.arizona.edu/our-work/research-policy-analysis/indigenous-data-sovereignty-governance; Lopez, J. D. (2021). Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Quechan education data sovereignty. In Walter, M., Kukutai, T., Carroll, S. R., & Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. (Eds.), Indigenous Data Sovereignty and policy (pp. 148–156). Taylor & Francis; and Data Quality Campaign. (2023, February). Data can support tribal sovereignty. https://dataqualitycampaign.org/resource/data-can-support-tribal-sovereignty/

13 Lopez, J. D. (2021). Examining construct validity of the scale of Native Americans Giving Back. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 14(4), 519–529.

14 Data Quality Campaign. Data can support tribal sovereignty.

15 Lopez, J. D. Indigenous Data Sovereignty.

16 Jones, N., Marks, R., Ramirez, R., & Ríos-Vargas, M. (2021, August 12). 2020 Census illuminates racial and ethnic composition of the country. United States Census Bureau (website). https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html

17 Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data, 62 FR 58782; and IES-NCES (website). Collecting race and ethnicity data from students and staff using the new categories.

18 Maxim, R., Sanchez, G. R., & Huyser K. R. (2023, March 30). Why the federal government needs to change how it collects data on Native Americans. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-the-federal-government-needs-to-change-how-it-collects-data-on-native-americans/

19 Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, 89 FR 22182.

20 Lopez, J. D., & Marley, S. C. (2018). Postsecondary research and recommendations for federal datasets with American Indians and Alaska Natives: Challenges and future directions. Journal of American Indian Education, 57(2), 5–34. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/jamerindieduc.57.2.0005)

21 Lopez, J. D. (2020). Indigenous data collection: Addressing limitations in Native American samples. Journal of College Student Development, 61(6), 750–764. doi:https://experts.arizona.edu/en/publications/indigenous-data-collection-addressing-limitations-in-native-ameri

22 Information shared with IHEP by University of California Office of the President staff on April 25, 2024. https://admission.universityofcalifornia.edu/

23 Lopez, J. D. Indigenous data collection.

24 National Congress of American Indians (2020). Tribal Nations and the United States: An introduction. https://www.ncai.org/about-tribes

25 Evans-Lomayesva, G., Lee, J. J., & Brumfield, C. (November 2022). Advancing American Indian & Alaska Native data equity.

26 Greyeyes, J., Begaye-Tewa, R. L., Brown, K., Begay, N., Tachine, A. R. (2023, April 1). College affordability for Native college students. Stanford Public Scholarship Collaborative. https://publicscholarshiptestonly.sites.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj28081/files/media/file/psc-brief-2-edited_0.pdf

27 Oregon Student Aid (website). Oregon Tribal Student Grant. https://oregonstudentaid.gov/grants/oregon-tribal-student-grant/#:~:text=The%20Oregon%20Tribal%20Student%20Grant,the%202022%2D2023%20academic%20year%20%20

28 The University of Arizona (website). Scholarships and Financial Aid: Funding for Indigenous Wildcats. https://financialaid.arizona.edu/types-of-aid/funding-for-indigenous-wildcats#tribal-enrollment

29 Pate, N. (2023, July 18). College tuition breaks for Native students spread, but some tribes are left out. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/college-tuition-breaks-for-native-students-spread-but-some-tribes-are-left-out/

30 IES-NCES (website). Digest of Education Statistics. Table 702.12. Percentage distribution of children ages 3 to 18, by whether they have home internet access, whether they have access through computer or only smartphone, and selected child and family characteristics: 2019 and 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_702.12.asp

31 American Indian Policy Institute. (2020). Tribal digital divide policy brief and recommendations. Arizona State University. https://aipi.asu.edu/sites/default/files/tribal_digital_divide_stimulus_bill_advocacy_04032020.pdf

32 National Indian Education Association. (n.d.) National landscape of postsecondary pathways for Native students. https://www.niea.org/higher-education

33 IES-NCES (website). Enrollment trends by race/ethnicity and gender, 2021–22. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/SummaryTables/report/1000?templateId=100001&years=2022&expand_by=0&tt=aggregate&instType=1&sid=20cf6e97-62b7-4c66-aff0-f128c17ea0d6

34 Falkenstern, & Rochat. Better data for supporting American Indian/Alaska Native students.

35 In some circumstances, such as when differences between subgroups are particularly large, researchers can draw statistically valid conclusions from small sample sizes. In those cases, researchers should report thorough findings for AI/AN students. Also, increasing AI/AN sample sizes in research is only the first step to mitigating sampling errors. Stratified sampling of Tribal Nations is also critical to minimizing errors and ensuring the sample is representative of multiple Indigenous communities.

36 Reyes, N. A. S., & Shotton, H. J. (2018). Bringing visibility to the needs and interests of Indigenous students: Implications for research, policy, and practice. The Association for the Study of Higher Education, National Institute for Transformation and Equity, and Lumina Foundation. https://nite-education.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Bringing-Visibility-to-the-Needs-and-Interests-of-Indigenous-Students-FINAL-2.pdf

37 Data Quality Campaign. Data can support tribal sovereignty.

38 U.S. Census Bureau (website). History: Censuses of American Indians. https://www.census.gov/history/www/genealogy/decennial_census_records/censuses_of_american_indians.html

39 Lopez, J. D. Indigenous Data Sovereignty.

40 Burnette, J. D. (2021). Why is the total enrollment of American Indian and Alaska Native precollegiates such a difficult number to find? Journal of American Indian Education, 60(1), 162–186.

41 Evans-Lomayesva, Lee, & Brumfield. Advancing American Indian & Alaska Native data equity.

42 Lopez, J. D. (2020). Indigenous data collection: Addressing limitations in Native American samples. Journal of College Student Development, 61(6), 750–764. doi:10.1353/csd.2020.0073; and Cherokee Nation (website). Osiyo! https://www.cherokee.org/

43 Greyeyes, Begaye-Tewa, Brown, Begay, & Tachine. College affordability.

44 Greyeyes, Begaye-Tewa, Brown, Begay, & Tachine. College affordability.

45 Walter, M., Carroll, S. R., Kukutai, T., & Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. (2021). Embedding systemic change—Opportunities and challenges. In Walter, M., Kukutai, T., Carroll, S. R., & Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. (Eds.), Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Policy (pp. 226–233). Taylor & Francis.

46 National Advisory Council on Indian Education (NACIE). (2023, August). 2022–2023 annual report to Congress. https://oese.ed.gov/files/2023/08/NACIE-AnnualReport2023-508_completed.pdf

47 Lopez, J. D. Indigenous Data Sovereignty.

48 Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, 89 FR 22182.

49 Indigenous Education State Leaders Network and American Institutes for Research. 2023. Indigenous students count: A landscape analysis of American Indian and Alaska Native student data in U.S. K-12 public schools. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/Indigenous-Students-Count-report-2023.pdf

50 Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) Form, July 1, 2024 – June 30, 2025. https://studentaid.gov/sites/default/files/2024-25-fafsa.pdf

51 Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, 89 FR 22182.